Extraordinary Life & Times of Lee Iacocca

Famed automotive mogul Lee Iacocca passed away July 2 in his Bel Air, California home at the age of 94. The news was met with an outpouring of reaction and memories shared by automotive figures, friends and former colleagues.

“Lee Iacocca was truly bigger than life and he left an indelible mark on Ford, the auto industry and our country,” said Bill Ford, executive chairman for Ford Motor Co. “Lee played a central role in the creation of Mustang. On a personal note, I will always appreciate how encouraging he was to me at the beginning of my career. He was one of a kind and will be dearly missed.”

FCA also issued the following statement: “(Iacocca) played a historic role in steering Chrysler through crisis and making it a true competitive force. He was one of the great leaders of our company and the auto industry as a whole. He also played a profound and tireless role on the national stage as a business statesman and philanthropist. Lee gave us a mindset that still drives us today-one that is characterized by hard work, dedication and grit-¦His legacy is the resiliency and unshakeable faith in the future that live on in the men and women of FCA who strive every day to live up to the high standards he set.”

Lisa Copeland, a former automotive executive who worked for Chrysler during Iacocca’s reign as CEO, shared these thoughts: “Perhaps what’s even more remarkable, and a lesson we can all learn from, is that he defined and built his success all by himself. Raised by a dad who was the son of an immigrant hot-dog vendor, he quickly worked his way up the ranks at Ford starting out in sales.

“One of the things I will remember most was his bold leadership style,” Copeland added. “Iacocca said things like they were and was a true visionary and innovator. He even told consumers, ‘If you can find a better car, buy it!’ He would make promises and delivered.”

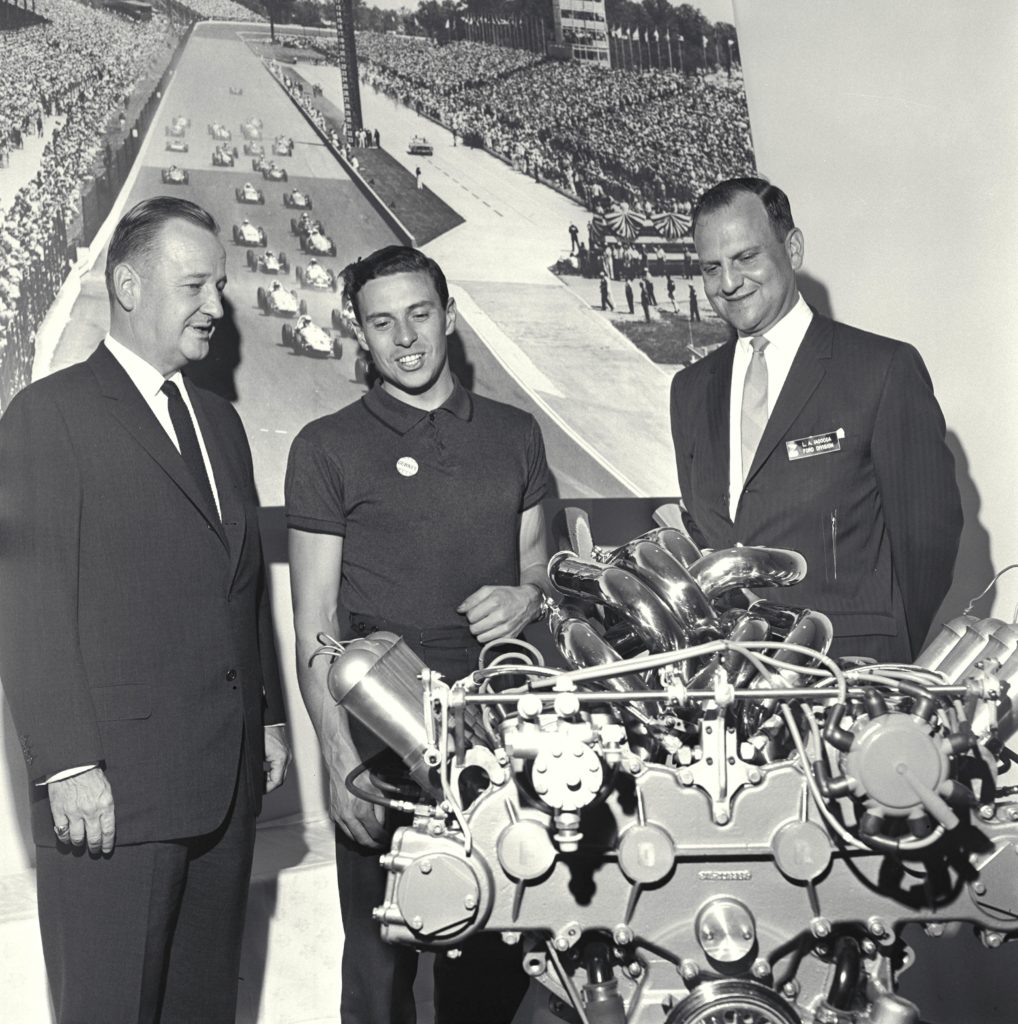

Lee Iacocca was the first in Ford’s upper management to promote an all-out, all-encompassing racing program, later called Total Performance. Iacocca is pictured here (left) with his marketing man Frank Zimmerman (right) at a race track. He and Zimmie were friends going all the way back to 1946 when they were fellow Ford trainees.

Start of an Extraordinary Career

Lido Anthony Iacocca came from Allentown, Pennsylvania.

By the time he was 15 years old, he wanted to be in the car business, influenced by his father’s friend who had a car. His father also ran a local car rental agency and wanted his son to get involved with the business. With the rental business in mind, Iacocca earned an industrial-engineering degree at Lehigh University and went on to Princeton for his master’s.

Before graduating, Iacocca started at Ford Motor Co. at the bottom. He was a student engineer, seeing duty on the assembly line. His first Ford paycheck came in 1946, for $37.40.

Nine months into a program designing Ford automatic transmissions, Iacocca decided clutch springs was not his thing. He wanted to sell cars.

He transferred into the sales department and started going by the name Lee, which he thought was easier for people pronounce, especially since he had a tongue-twisting last name.

Surrounding famed race driver Jim Clark in a pre-race photograph taken prior to the 1964 Indy 500, Benson Ford (left) and Lee Iacocca (right) view the new Ford overhead cam race engine, which powered to the win at the 1965 Indianapolis 500, the first win for a rear-engine car at the brickyard.

Life of a Salesman

In 1953, Iacocca was the assistant sales manager in Ford’s Philadelphia sales district. He learned Ford’s sales tactics but began experimenting with his own ways of selling and promoting new products.

For the 1956 model year the big sales angle was safety. Iacocca had seen a factory promotional film about how great the new safety padding was on the 1956 Ford dashboards. The film pointed to dash padding so thick it would save a dropped egg from cracking-from a two-story building, no less. It inspired Iacocca try his own egg drop, a promotional idea he pitched to about 1,100 men attending a regional sales meeting.

With cameras rolling, it took about five tries for a successful egg drop-but it earned Iacocca a standing ovation from the audience watching.

“I had plenty of egg on my face that day,” he said. “And it turned out to be a prophetic symbol for our 1956 cars. The safety program was a bust. Our campaign was well conceived and highly promoted, but the consumers failed to respond.”

The license plate reads 417 by 4/17 on an early production 1964 1/2 Mustang, with Lee Iacocca and Donald Frey proudly standing next to it. At this stage in time, nobody knew the unreal success that was coming for the new pony car from Ford.

Marketing Chops-¦and Chips

Iacocca’s next big idea had to do with a different kind of food: potato chips. He dreamed up a marketing concept after figuring out a brand-new 1956 Ford would cost just $56 per month for three years after a 20-percent down payment.

The 56 for ’56 campaign soon rolled out in Philadelphia. Iacocca and his salesmen visited local supermarkets and placed a small bag of potato chips on car windshields with the note reading, “The chips are down, we’re selling cars for $56.00 per month.” The note also asked car owners if they’d be willing to trade up for a new Ford.

The marketing gimmick elevated Iacocca’s sales district from the worst performing to the best. Robert S. McNamara, president of Ford, noticed. The campaign was adopted nationwide-minus the chips-marking the beginning of Iacocca’s rise.

McNamara said the 56 for ’56 campaign led to an additional 75,000 Fords being sold.

Just like that, Iacocca became Ford’s new marketing manager for trucks, moving to Dearborn, Michigan in late 1956.

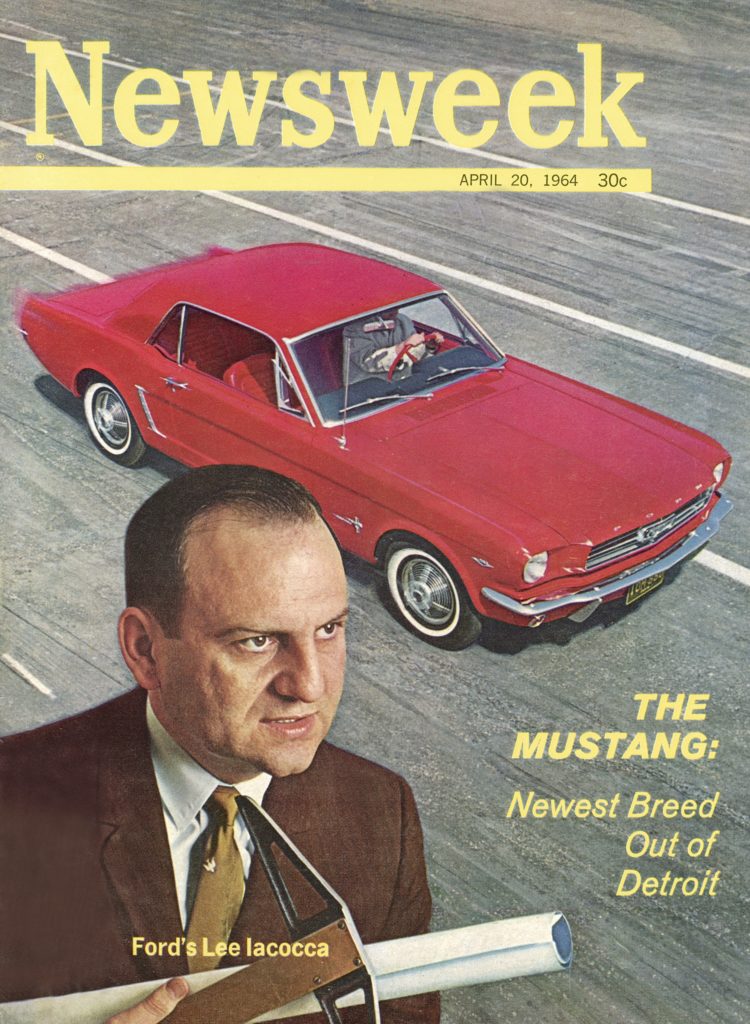

Both the Newsweek and Time magazines featured the Mustang on their covers in April 1964. The rival publications both featured head shots of Iacocca with the new Mustang in the background.

Selling Speed

Iacocca tried selling safety, but ultimately racing was the answer.

“Gave the safety thing hell; I promoted it for all it was worth, but the Chevy V-8 was beginning to take off, and they were promoting that,” Iacocca remembered. “What I learned was simple: a puppy’s got to like what he’s being fed.”

The 1960 Ford Falcon was the brainchild of McNamara. It was a sales success with some 417,000 units sold in the first year. The car represented a paradigm shift in Detroit, and it also stymied losses from the disaster that was the Ford Edsel.

“McNamara believed in basic transportation without gimmicks,” Iacocca said, “and with the Falcon he put his ideas into practice. Although I didn’t care for the car’s styling-I don’t really think it had any-I had to admire its success.”

Meanwhile, Iacocca had been promoted to vice president and general manager of the Ford Division in1960. His career was officially on a fast-track. Horsepower and performance were the themes of 1962 and Iacocca was the guy to approve the new and aggressive Ford racing program. The company’s racing involvement included the Holman & Moody teams in stock car racing, an entry into Indy car racing, as well as large amounts of attention given to drag racing, rally racing, endurance racing and eventually Formula 1.

Iacocca loved the excitement of racing and got Fords on all the major race tracks across the world. Ford’s presence generated a good deal of attention from the media, something Iacocca knew would help sell vehicles.

During the 1968 model year run Ford built its 2 millionth Mustang and Iacocca was on hand when it rolled down the assembly line.

Shelby & Mustang Emerge

The Ford Mustang was a huge risk for the company but also for Iacocca.

In late 1960 Henry Ford II had just dealt with one of the company’s biggest failures with the Edsel, and was staring down another with the ill-fated Cardinal. Iacocca talked Ford II out of pursuing the Cardinal and put his job on the line for the Mustang.

“In late 1960, when I became the Ford Division general manager, I was in a position to investigate whether producing such a car was feasible. We had no data, but I felt there was a market to be driven by baby boomers,” Iacocca recalled.

The Chevrolet Corvair Monza helped spark Iacocca’s interest in producing a car that appealed to a youthful audience. During early stages of Mustang development, a guy named Carroll Shelby came to Dearborn seeking an engine for a car he was trying to get off the ground-the Cobra. Iacocca agreed to supply the brand-new 260-cid V-8 engines to Shelby on credit.

“It was Lee Iacocca who really stayed behind us all the way,” Shelby told writer Alex Gabbard in 1990. “He encouraged us and then got us into the Mustang program.”

After the 260-cid and 229-cid Ford V-8-powered Cobras got so much positive ink and attention for Ford, Iacocca brought Shelby into the company’s front office in 1965 to add some needed pizzaz to the Mustang.

Shelby added glitz and glamour to Ford Motor Co. but it was Iacocca who continued to push racing. He approved the huge expenses funding Shelby’s work, which included engines, drivelines, factory technical assistance and a full racing budget.

Mustang sales during its first two years generated $1.1 billion in net profits, an unreal number considering it was built on the cheap with a $45 million budget. A typical car at that time was developed with a $250-$300-million budget.

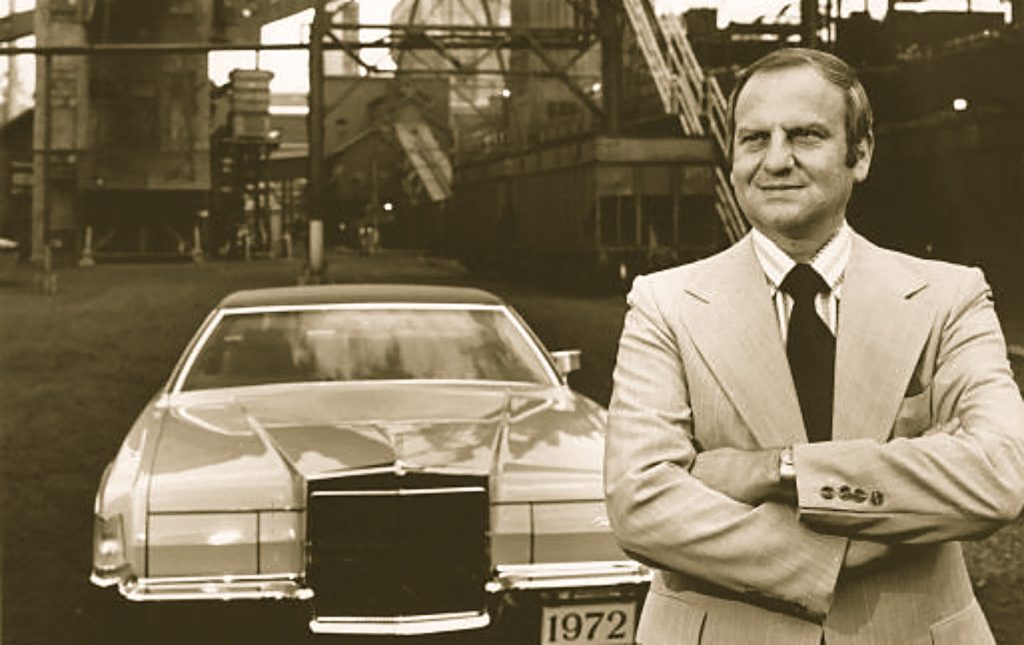

“Put me a Rolls-Royce grille on a Thunderbird,” Iacocca requested for the 1969 Lincoln Continental Mark III .

Lincoln Mark III & Maverick

A few years after the Mustang changed the automotive world, Iacocca found himself sleepless and in Canada on a business trip. Suddenly a vision flashed in his head and he immediately called Ford’s head of design, Gene Bordinat.

“Put me a Rolls-Royce grille on the front of a Thunderbird,” he said.

The resulting 1968 Lincoln Mark III turned out to be a real money maker for the division and another feather in Iacocca’s cap.

Maverick was another hit for Iacocca. Labeled as an import-fighter, it was larger than a Volkswagen Beetle. It was the right car at the right time for Ford Motor Co. Nearly 579,00 Maverick units were sold for the 1970 model year-exactly five years to the day after Mustang was introduced in 1969.

The Ford Pinto for 1971 was the company’s answer to the Volkswagen Beetle, a car targeted for weight below 2,000 pounds and cost no more than $2,000. It was a huge sales success with more than 3.1 million were sold. The sub-compact was Iacocca’s baby, but its reputation was marred because of rear-end explosions when collisions occurred

Pinto Problems

On Dec. 10, 1970, Iacocca was given the title of president of Ford, top man leading some 432,000 employees. Things had changed in the American automotive manufacturing world, and small cars were surging. Ford’s answer was the sub-compact Pinto, which would compete against the VW Bug.

The Pinto, known as Lee’s car, was rushed into production after 25 months, compared to 43 months, which was typical for Ford at the time. The Pinto, however, had a serious defect with the design of the fuel tank, and a number of other problems later to emerge.

The fuel tank in the Pinto was located between the rear bumper and the differential, commonplace for other vehicles at the time. However, when a rear collision occurred the mounting bolt on the right-rear shock absorber would pierce the fuel tank. At the same time, the filler neck on the left side of the car would break away from the tank causing gasoline to spray around the area. One spark would create a rolling inferno. Reports suggest that between 27 to 180 people died due to the design blunder, according to Popular Mechanics.

“Believe me nobody sits down and thinks, I’m going to make this car unsafe,” Iacocca later wrote in his memoirs. “The guys who built the Pinto had kids in college who were driving the car.”

Iacocca took responsibility for the Pinto’s failures. In 1978, the company agreed to recall 1.5 million Pintos, along with 30,000 Mercury Bobcats, Pinto’s sister car. But it was too late-”the Pinto was a PR disaster and Ford’s reputation was damaged.

Worse yet, a landmark court case in 1979 led the automaker to becoming the first U.S. corporation indicted and prosecuted on criminal homicide charges.

The smile on Lee Iacocca’s face in this shot standing next to Bunkie Knudsen may not have been real sincere, as he was far from happy when Henry Ford II hired him from General Motors to become Ford’s new president in February 1968.

Fuel Crises

Big muscle and V-8 power wasn’t in demand by late 1973, when the first U.S. oil crisis happened. Though not remembered for being a remarkable car, the more fuel-economic Mustang II, proved to be the right car for Ford when it hit showrooms.

Iacocca pushed through the release of another all-new Ford car in 1974: the Granada and the matching Mercury version, Monarch. They were built from the four-door Maverick platform, updated with an exterior arguably inspired by Mercedes-Benz.

The impressive sales figures reached 302,649 units for the Granada and 104,000 for Monarch.

The next Lincoln that was released with the Rolls-Royce grille after the Mark III was the even larger Mark IV that debuted as a 1972 model.

Abrupt Ending

Iacocca’s career at Ford ended with a dispute with Henry Ford II. Walter Hayes, a long-time Ford employee, spilled the beans about the drama in his 1990 book, Henry, A Life of Henry Ford.

“It was while Henry was in China that Lee Iacocca decided upon a coup,” Hayes wrote.

Iacocca tried to convince Ford board members that Ford II was senile and that others in the company shared his opinion. Arjay Miller, close friends with Ford II and a former president of the company, got wind of the coup and informed Ford II.

At a 1978 board meeting, Ford II reportedly said, “When a man does what Iacocca has done when my back was turned, I have no alternative but to seek a vote of confidence. It’s either me or Iacocca.”

Iacocca was fired the next day, instantly becoming the hottest free agent in the automotive market.

Ford II resigned as CEO in 1979 and resigned as chairman in 1980.

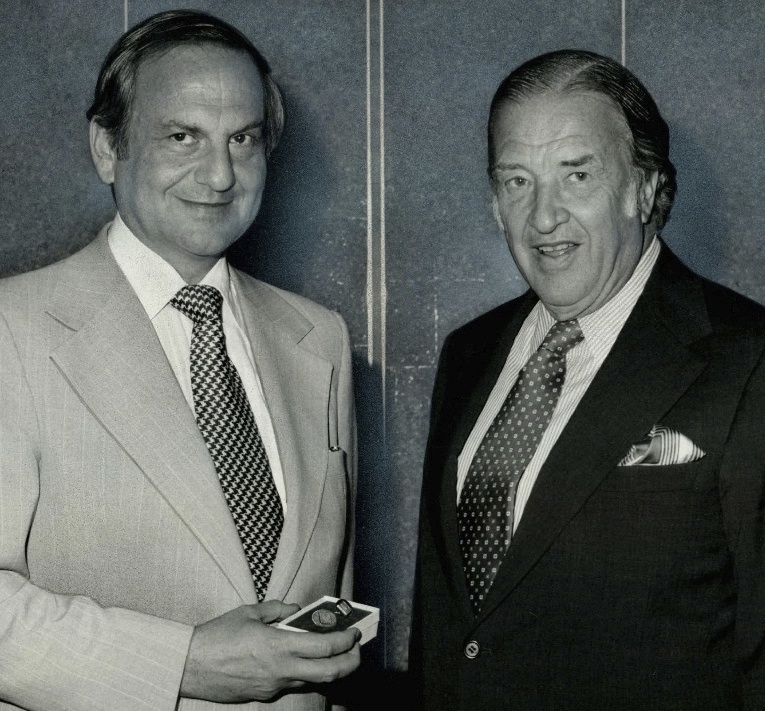

While they both might look somewhat happy and friendly here on July 13, 1978, Henry Ford II told Lee Iacocca that the Ford Motor Co. no longer needed his services. When Iacocca pressed him for a more exact explanation, it is said that Henry II told him that “sometimes you just don’t like somebody.” And that was that.

Surprise Landing

Iacocca was quickly scooped up by the struggling Chrysler. Next to headlines announcing his appointment on Nov. 2, 1978, Detroit Free Press carried the inconspicuous headline, Chrysler Losses Are The Worst Ever. Chrysler had lost $160 million in the third quarter, the newspaper noted.

Part of Chrysler’s problems at the time were the Dodge and Plymouth Aspen and Volaré lines, which replaced the venerable Dodge Dart and Plymouth Valiant and Duster. The Mopars were suffering from extreme quality control problems, costing the corporation loads of money to costly vehicle repairs.

Another root of the company’s problems was a thing known as the sales bank, created when the factory kept building unsold cars to keep assembly workers busy. These cars were stored outside for long periods of time.

“In the summer of 1979,” Iacocca recalled, “the number reached as high as 100,000 units, representing $600 million!”

The K-Car is the new platform that helped save Chrysler. Here’s Iacocca with a LeBaron convertible complete with hide-a-way headlights.

Changing Chrysler

Under Iacocca, Chrysler brought in a new advertising agency, plants were closed, and some Chrysler assets were sold, including the Tank Division with had profitable government contracts. “I was tempted to sell off the car business and keep the tanks,” Iacocca said in 1984. “Financially that would have made a lot more sense. But building tanks was not our main line of business. If Chrysler was going to have a future, it would have to be a car company.”

The advertising agency injected some life into the truck division by bringing back the Ram Tough symbol.

Iacocca also secured funding for new-vehicle development, including the K-Car.

Actor Ricardo Montalban was commonly seen in Chrysler TV commercials.

Running Ragged

Iacocca’s tireless search for funding led Chrysler to request a loan from the U.S. government. He convinced Congress to green-light the loan, saying it would be paid back early-but Iacocca’s efforts took a toll on his health

“During the last three months of 1979,” he shared in his book Iacocca, “the pressure on me was tremendous. I was going to Washington a couple of times a week and trying to run Chrysler at the same time. I was on a crazy schedule of eight or 10 meetings a day.

“Once I was walking down one of the marble corridors in Congress and I just didn’t feel right. It was as if I was walking on eggs. I was dizzy and close to fainting. I was also seeing double. They took me to the surgeon general’s office, where they checked me out-it was vertigo. They discharged me, but then it happened again. All the tension and pressure made me feel like I had rocks in my head. But somehow I muddled through.”

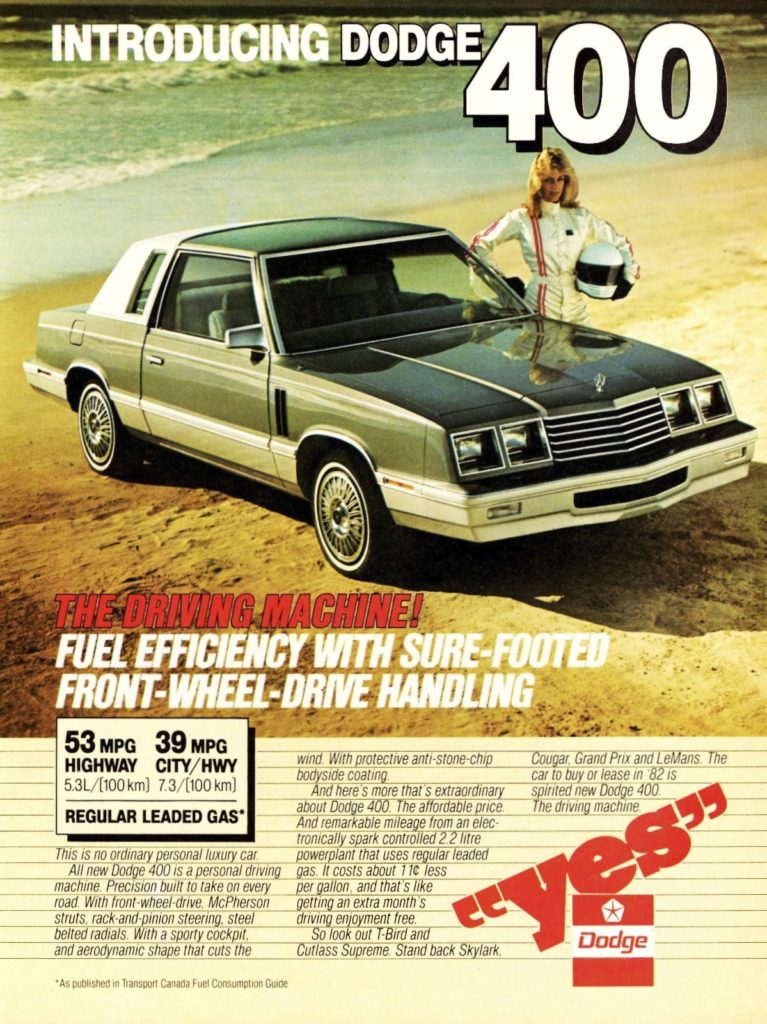

Touting 53 highway miles per gallon, the Dodge 400 version of the K-Car was introduced for the 1982 model year and was promoted as a personal driving machine.

$50 Test Drive

Iacocca’s brought his signature marketing flare to Chrysler. One campaign-the $50 test drive-was particularly daring. It offered customers who test drove a new Chrysler, Plymouth or Dodge vehicle $50 if they decided to buy a rival vehicle.

Another innovative idea originating from Iacocca was to give new-car buyers 30 days with the car before deciding whether or not to keep it. Chrysler promised a full refund-save for a $100 fee-if customers didn’t want the car.

“To the surprise of the skeptics,” Iacocca recalled, “the program worked very well. Most people play fair; very few took advantage.”

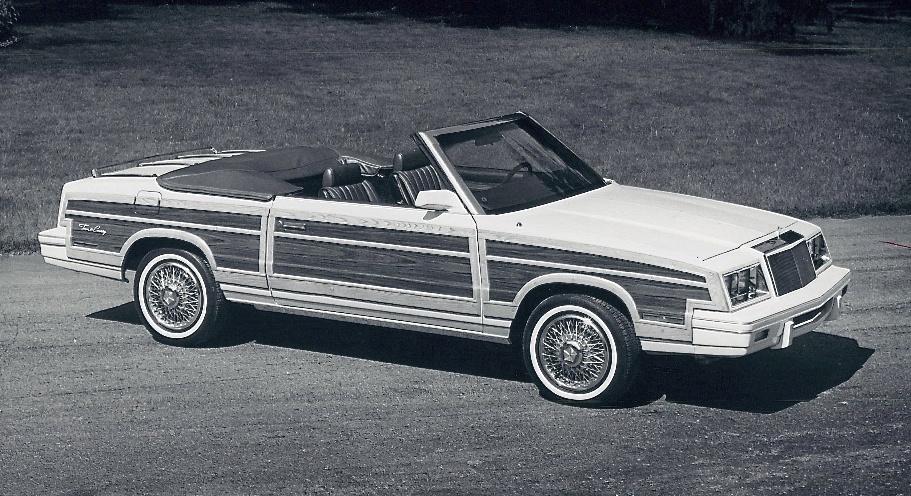

Iacocca was walking through the design studio one day when he saw the prototype Town & Country K-Car wood-sided convertible, built as a design study. He stopped and said, “I want this car.” They were made available to the buying public for 1983-1986 model years.

Saves The Day

Arriving just in time to keep Chrysler in business was the 1981 K-Car. The car’s platform was based on the Dodge Aries and Plymouth Reliant, and eventually led to the Dodge 400 and Chrysler LeBaron. It featured front-wheel drive and an economical transverse engine.

New Your Times had this to say in 1984 about the K-Car: “It not only single-handedly saved Chrysler from certain death, it also provided the company with a platform that could be stretched, smoothed, poked, chopped and trimmed.”

By 1983 K-Car and its variants represented 55 percent of Chrysler’s full passenger car sales.

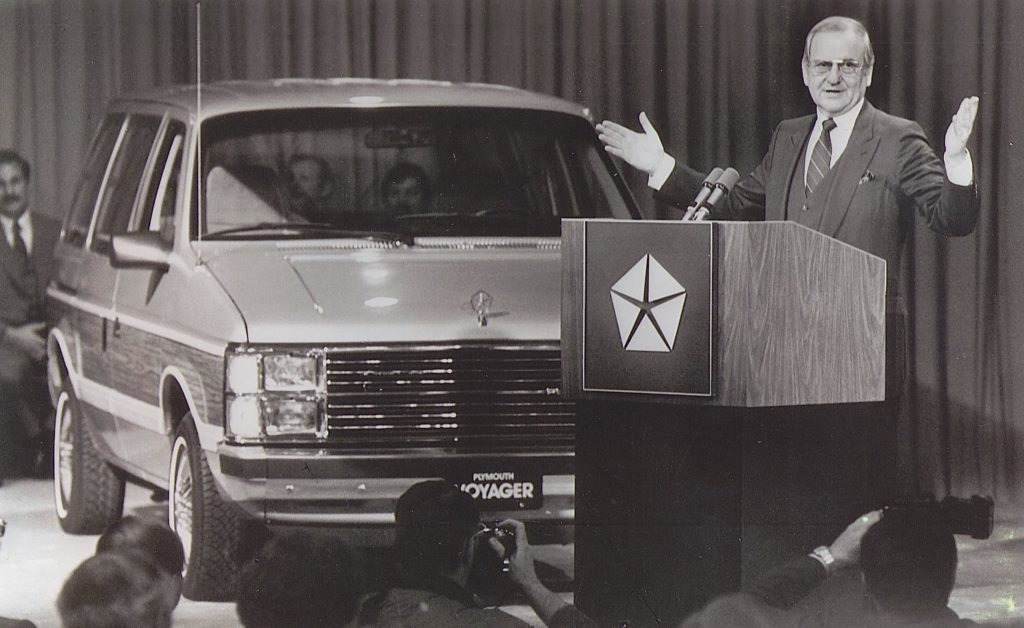

The invention of the mini-van may have taken place at Ford a few years earlier, but the actual production of the brand-new vehicle segment happened at Chrysler. Iacocca believed in the project that was the brainchild of product planner Hal Sperlich.

Speedy Recovery

Right as things were looking up for Chrysler, Iacocca put a call in to his old pal Carroll Shelby. Shelby helped bring swagger back to the brand by helping develop truly fast four-cylinder Dodges, including the Omni GLH (Goes Like Hell), GLHS, and Dodge Viper in 1988.

Like the Cobra in the ’60s, Iacocca was directly involved in the Viper’s release-it was powered by a re-worked V-10 engine originally slated for Ram trucks.

Legend has it that Iacocca gave the Viper prototype a test blast on the streets of Detroit.

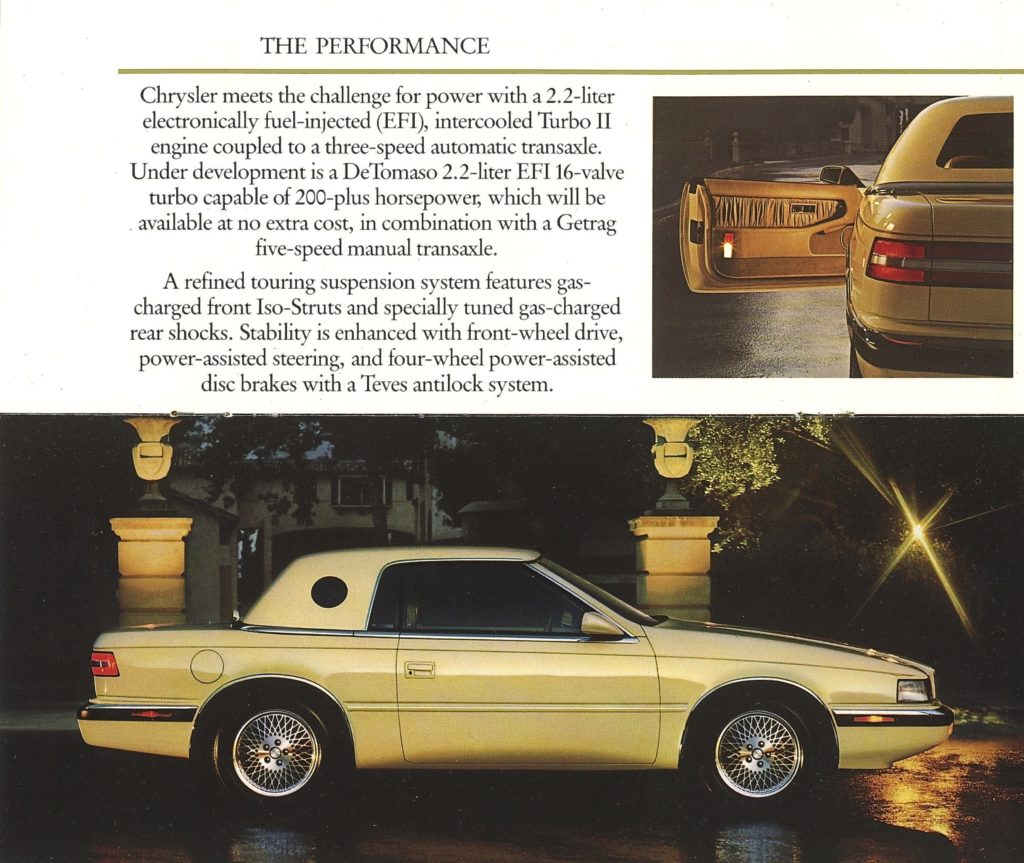

The TC by Maserati Q-body cars built from 1989-1991 in Italy and sold at Chrysler dealers in America. Unfortunately, the cars ended up looking close to the much less expensive Chrysler LeBaron GTC convertible. TC was short for Touring Convertible. The cars were the result of Iacocca wanting to use the K-Car and combine it with Italian style, to add flash, to change the way the world looked at the line of Chrysler vehicles as a whole. The detachable hardtop and round porthole windows were an obvious throwback to the early Thunderbirds.

Jeep Investment

Iacocca’s dream of owning the Jeep brand was realized in 1987 when Chrysler purchased American Motors, which owned the off-roading nameplate.

“Jeep is the best-known automotive brand in the world,” Iacocca said at the time. The purchase was a significant factor in Chrysler’s continued success-the ZJ Jeep Grand Cherokee became the most awarded SUV ever-enhancing Iacocca’s legendary reputation.

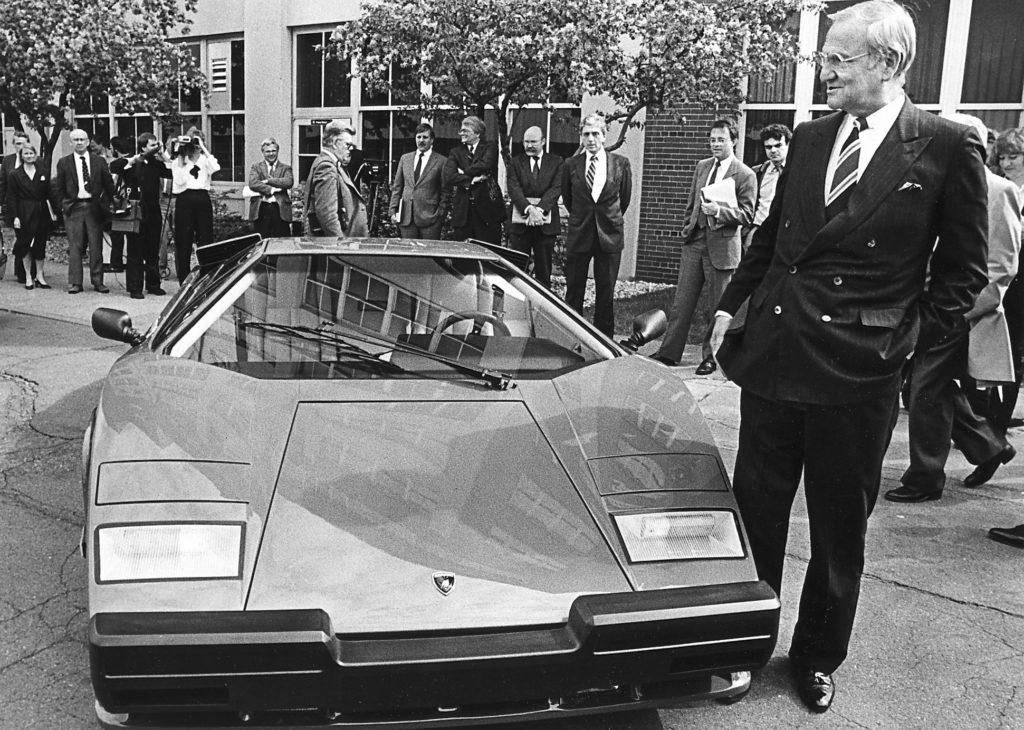

On April 23, 1987, Chrysler Corp. purchased Nuova Automobili F. Lamborghini for an estimated $25 million with the idea being that it would provide a valuable arm in the exotic car marketplace. Here’s Iacocca with a Countach model at the press gathering to celebrate the event.

A New Kind of Car

Even before Iacocca joined Chrysler, he and Ford colleague Hal Sperlich wanted to create an entirely new type of vehicle: the mini-van. Ford’s plans to make the Minimax never took off, but the timing was right at Chrysler. The T-115 Dodge Caravan was born, representing a huge breakthrough for the company. The Plymouth Voyager and Town & Country came soon after.

“Hal Sperlich lured me to Chrysler,” Iacocca told writer David E. Davis in 2005. “Hal was on the original Mustang team at Ford-he had a nose a genius for looking at the whole inventory of platforms and components, bringing combinations together, and getting them to market. He was just great at it. He used to drive me nuts. He pushed me harder on the Mustang than anybody, and he pushed me on the minivan.

“We called it the Minimax at Ford-the front-drive van that drives like a car and fits in a normal garage. All the research indicated it would be a winner. Sperlich pushed so hard that Henry Ford made me fire him, and he went to Chrysler-wound up holding the door open for me there.”

The minivan was an instant hit, and now commands about 30 percent of the world market.

After Iacocca was inducted into the Walter P. Chrysler Legacy Circle in 2010 he told one reporter that he considered the minivan his career’s greatest accomplishment.

Jay Leno is a big fan of Lee Iacocca as seen here at a Mustangs in the Park gathering in Van Nuys, California.

Setting an Example

Iacocca shared some other rare insights with writer David E. Davis in his 2005 interview, including how he shook additional funds loose from Chrysler’s executive team.

“Chrysler didn’t have any money. They were broke. I needed a loan guarantee from Congress, but we had to get our house in order first. We installed Ford-style financial controls, went to work cleaning up the fields full of unordered, unsold new cars.

“I went to the United Automobile Workers to ask for their help. I got lucky on that one. Doug Fraser was there. He’d come up through the ranks, and he was a solid, standup guy. I’d worked with him before.

“I said, ‘Guys, it’s simple. It’s a cold winter night, and I’ve got about 300,000 jobs at 15 bucks an hour. At 20 bucks an hour, I’ve got none. What do you want to do?’

“Doug said, ‘What are you gonna do?’

“I told them we’d start with the executives and give everybody a 20-percent haircut. He said it again, ‘What are you gonna do?’

“I said, ‘I’ll work for a buck a year.'”

That night, the bargaining council said if Iacocca was willing to work for nothing, they’d take pay cut too-they gave back $2.5 billion.

“Nobody ever gives the UAW enough credit in its role in the bailout,” Iacocca told Davis. “We paid back the loans in 36 months and paid the government a profit of $350 million for its help. And after that, Chrysler was a brand-new car company.”

When Jay Leno interviewed Iacocca in 2015 to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Mustang, he said that “Iacocca was the car salesman’s car salesman, he was the best there was.” Iacocca was truly that, and so much more.